When teachers work together bringing forward evidence from student learning to improve classroom practice and learning, they’re tapping into the most important source of instructional improvement in schools –teacher-to-teacher professional learning and collaboration. Some of the most important forms of professional learning occur in daily interactions among teachers – whether it’s improving lessons, deepening understanding of content, analyzing student work or examining student performance .

The central challenge faced by all leaders is to create situations that promote teacher learning about teaching practices that make a difference for students. This kind of knowledge-building work must become the core business of school leaders .

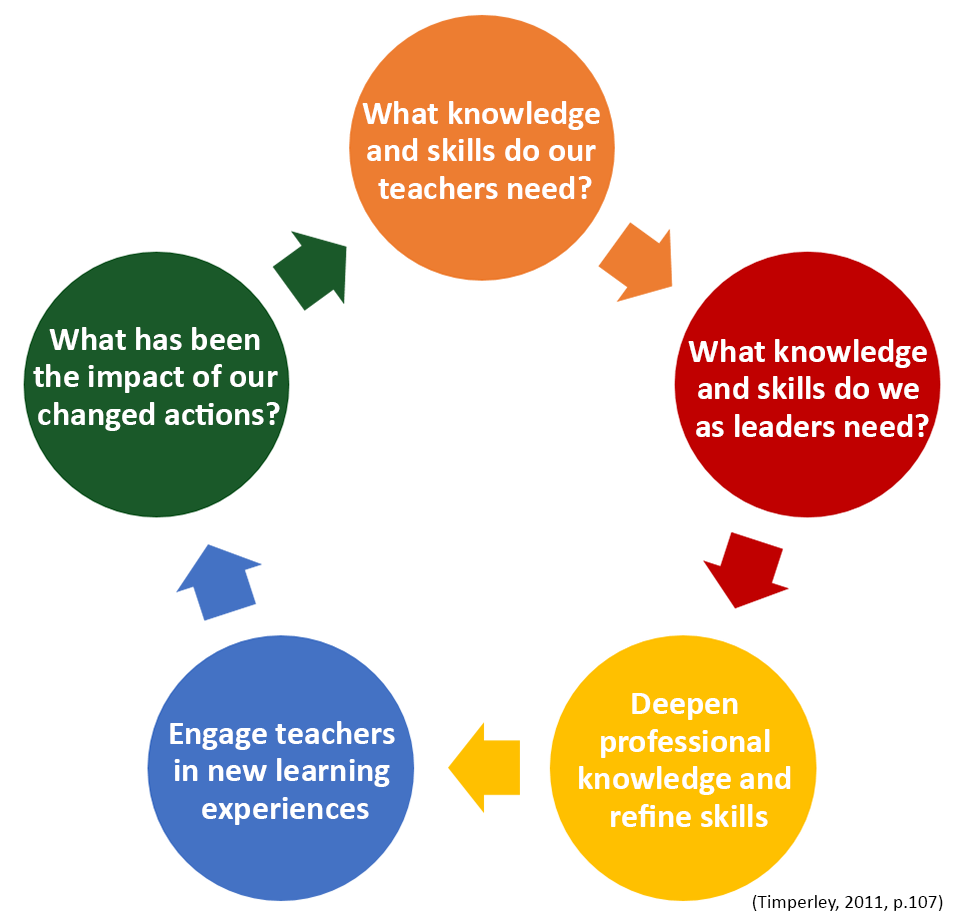

One approach to building knowledge could be to help teachers learn how to diagnose the learning needs of individual students and how to teach them in specific ways, together with finding out why particular approaches and strategies were more likely to work than others. This type of knowledge building is very specific to the students and the task at hand. At the same time, the knowledge is developed in ways that teachers could use it with other students and situations. When professional learning is focused on cycles of inquiry into students’ needs, then making changes in students’ learning environments becomes an integral part of building knowledge .

Of course, this is only realized when positive and respectful relationships are cultivated – amongst teachers and between teachers and principals/leaders.

Relationships between teachers and leaders are central to well-functioning schools. They are the platform from which school improvement and improvement in student learning takes off. For these relationships to succeed, trust and respect must become core values. Listening to others, having a willingness to extend beyond what is formally required, and believing that colleagues have the knowledge, skills and capacity to deliver on intentions and promises, all go a long way in both teachers and leaders feeling respected and acknowledged . In this environment, leaders can challenge teachers to think more about student outcomes, their practice, and what is needed when it’s evident change needs to happen. And teachers, through their own work, are committed to making this happen. Because everyone has the same goals, teachers aren’t targeted and made to feel that their practice isn’t ‘good enough’ – both teachers and leaders are working together to maximize and improve student learning.

“Leaders are the stewards of organizational energy…they inspire or demoralize others, first by how effectively they manage their own energy and next by how well they manage, focus, invest and renew the collective energy (resilience) of those they lead.”

Teachers need learning leaders who can provide the right support for, so that they in turn, promote their students’ learning. These leaders care about and focus on the learning needs of pupils and the professional growth of teachers, and work hard to enhance the role of the schools as an agent of social change. The quality of leadership matters in creating, developing and broadening intellectual social and emotional capital within and beyond the school and providing optimal conditions for resilience, commitment and effectiveness amongst staff. Supportive organizational communities don’t happen by chance. They require good leadership .

When leaders and teachers engage in ongoing inquiry and knowledge-building cycles, inquiry habits of mind become part of how things are done. These are habits of using inquiry and reflection to think about where you are, where you are going, and how you will get there – and then turning around to rethink the whole process to see how well it is working and make adjustments. It means things are focused, but sufficiently flexible to meet individual teacher and student needs as they are identified. Opportunities for professional learning reflect the structure and rhythm of what typically happens throughout the school day, week and year. Some are formal, and some are informal. Some are in school, and others out of class. Other opportunities for professional growth may be individualized and situated within student learning environments. All move in the same direction. Coherence across professional learning environments are not achieved through the completion of checklists and scripted lessons, but rather through creating learning situations that promote inquiry habits of mind throughout the school .

Indeed, engaging in inquiry and knowledge building cycles at all levels of the school organization is seen as core to professionalism – leaders and teachers become deeply knowledgeable about both the content of what is taught and how to teach it and create the organizational structures, situations and routines to develop it further. Everyone becomes aware of the assumptions underpinning their collective practice so they know when they are helpful and when to question them, and if necessary to let them go. They become expert in retrieving, organizing and applying professional knowledge in light of the challenges presented by the students they are teaching. The routines involve being constantly vigilant about the impact of leadership and teaching on students’ engagement, learning and well-being .

What else does this mean for teachers?

With an inquiry stance on leadership, teachers challenge the purposes and underlying assumptions behind educational change, rather than simply helping to specify or carry out the most effective methods for predetermined ends . As teachers investigate their practice more deeply, they adopt a scholarship of teaching. They’re doing more than transmitting information to students – they investigate, transform and extend knowledge, using the same habits of mind that characterizes the scholarly work found in the field of medicine or law, for example—the type of practice that is the hallmark of discipline-based inquiry .

Looking into practice and adopting a scholarship of teaching gives teachers the ability to self-reflect. To get to the fullest, deepest questions about teaching, educators will have to learn and borrow from a wider array of fields and put a larger repertoire of methods behind their practice .

What does this mean for leaders?

Just like teachers, school leaders need to engage in ongoing inquiry into the impact of their policies and practices. They need to identify personal learning goals and seek the appropriate response to achieving them. When it comes to the issue of teacher learning and improvement, an important question to ask is this: is the rhetoric around developing motivated professionals who can make informed decisions about their practice based on deep knowledge, but then contradicted by approaches to professional learning that involve brief workshops about how to teach something? . Teachers need learning leaders who can provide the right support for teachers to learn, so that they, in turn, promote their students’ learning. They need to work in a system that learns. And a system lift requires a systemic response.

The way schools are organized and run needs to be consistent with the broadening outcomes and the balance of, or selection between, the forces on them. Schools and their leaders will need to move from the bureaucratic and mechanistic to organic living systems, from thin to deep democracy, from mass education to personalization through participation, and from hierarchies to networks.

How to get there from here: school systems

Improving learning for students over an entire school system is a daunting task. Where do leaders begin? All too often, they’re told to start change efforts from a perspective or point different from their current reality. Educators in a moderately performing system, for example, are better off seeking inspiration from other moderately performing schools that are seeking to improve, rather than a system configured and positioned very differently, even if they are the among the best-performing systems in the world .

A small number of critical factors go together to create the chemistry of widespread improvement. A school system can develop and implement a journey to improvement, but to achieve success, these five points must be in place:

- The status quo, or performance stage, which identifies an awareness of where the system currently stands, while having an appreciation for the ongoing journey towards school and student improvement. It’s a snapshot of a moment in time. Student outcomes determine where a school system stands in relation to others.

- The intervention cluster, which is all about what is needed to make the desired improvement in student outcomes. Leaders must take into account the performance of the system currently, while deciding on interventions to improve performance while considering the socio-economic, political and cultural context in which they operate.

Peer-based learning through interactions that are school-based and system-wide, is one intervention that makes a great system become excellent. School systems that are struggling, however, would experience a different set of interventions – teaching is more tightly controlled and consistency in learning processes would be similar across all classrooms because minimizing variation is the core driver of performance improvement at this level.

What is common to all types of school systems seeking to improve, however, are interventions related to revising curriculum and standards, ensuring an appropriate reward and remuneration structure for teachers and principals, building technical skills, assessing students, establishing data systems, and publishing effective policy documents and the implementation of education laws.

- The system’s adaptation to the interventions, taking into account the history, culture, politics and structure of the school system and surrounding communities.

- Sustaining is all about ensuring improvement over the long term. School systems that do this have learned how to navigate the challenges of their context, or situation, and use it to their advantage. This is accomplished by a strong pedagogy supported by practices that are collaborative in nature.

How is this accomplished? Through the creation of an environment in which teachers and school leaders work together to embed routines that nurture instructional and leadership excellence. This includes making classroom practice public, and developing teachers into coaches of their peers. These practices are supported by an infrastructure of professional career paths that not only enable teachers to chart their individual development, but also make them responsible for sharing their skills across the system. Because these collaborative practices shift the drive for change to the front lines of schools, it causes system improvement to become self-sustaining.

Continuity in leadership is also an important sustaining factor. The most successful school systems actively foster the development of the next generation of system leadership from within.

- Ignition describes the necessary conditions that allow a school system to embark on its reform journey. The starting point for every school system embarking on improvement is to decide just how to overcome any present inertia. School systems that have successfully ignited reforms and sustained the momentum have all relied on at least three events to get them started: They have either taken advantage of a political or economic crisis, or commissioned a high-profile report critical of the system’s performance, or have appointed a new, energetic and visionary political or strategic leader.

In order for learning leadership, of which instructional leadership is a subset, to flourish – and with it, teaching, and system-wide school improvement, two important factors must be in place: A culture of creativity, which gives space for innovation to happen; and a system that fosters communication and understanding to ensure success, not stagnation, becomes reality.